Her last words were, “Ask Mr. Gaham to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country.”

Edith Cavell was born on December 4, 1865, in Swardeston, near Norwich, England. She worked as a governess, including a family in Brussels from 1890 to 1895. After caring for her father during a serious illness, Edith began a career in nursing.

In 1907, at the age of 42, Cavell was recruited to be the matron of a newly established nursing school in Brussels. She had a passion for training young women for the nursing profession.

When World War One broke out, her clinic and nursing school were taken over by the Red Cross. In November 1914, after Brussels was occupied by the German Army, Nurse Cavell began to shelter British soldiers and funnel them out of Belgium to neutral Netherlands. Subsequently, wounded French combatants and young civilian men were hidden from the Germans and given false documents. A kind of “underground railroad” was established in order to get these men to the Dutch frontier.

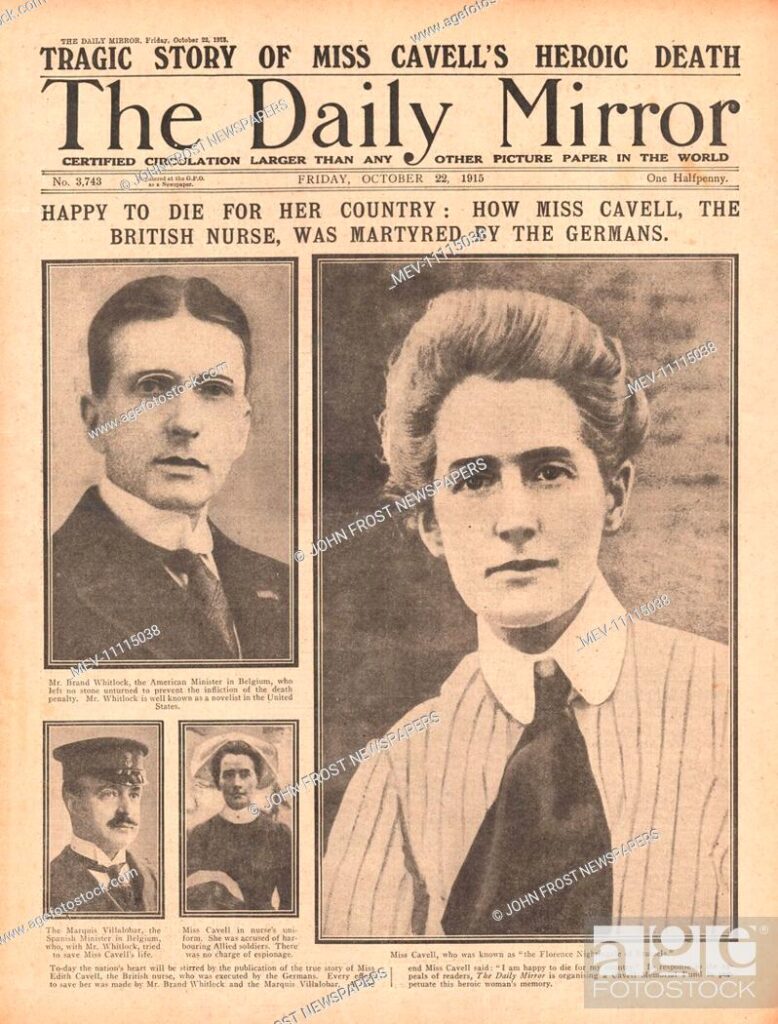

The German authorities became suspicious of Cavell and others. She was arrested on August 3,1915. She was betrayed by a French collaborator, Georges Gaston Quien. Edith was sent to Saint-Gilles prison for ten weeks. She admitted to harboring Allied soldiers during three depositions with German police.

At her court-martial, Nurse Cavell was prosecuted for aiding Allied soldiers and civilians. Also, it was established that she helped them escape to a country at war with Germany. The penalty, according to German military law, was death.

After her death sentence, the British government solicited the help of the American government to intercede on Cavell’s behalf, as America was a neutral country at the time. Hugh S. Gibson, Secretary to the U.S. Legation at Brussels told the German government that executing Cavell would further harm Germany’s tarnished reputation.

He wrote, ” We reminded (German civil governor Baron von der Lancken) of the burning of Louvain and the sinking of the Lusitania and told him that this murder would rank with those two affairs and would stir all civilized countries with horror and disgust. Count Harrach broke in at this with the rather irrelevant remark that he would rather see Miss Cavell shot than have harm come to the humblest German soldier, and his only regret was that they had not three or four old English women to shot”.

Although Miss Cavell had defenders against her execution in the German government, General von Sauberzweig, the military governor of Brussels, ordered that in the interests of Germany, the death penalty for Cavell should be carried out immediately, denying higher authorities an opportunity to consider clemency. In the end, Nurse Cavell was only one of two defendants executed out of the 27 to stand trial. She was convicted of war treason even though she was not a German national. On October 12, 1915, at 7:00 AM, she and another condemned, were placed in front of a firing squad. Cavell was given a blindfold, said her last words, and was shot by eight soldiers, killing her instantly.

Her execution was used by the British government as propaganda to portray the Germans as morally deprived. It was an effective campaign that moved many hearts in England, France, Belgium, and America.

According to the Reverend Gahan, an Anglican chaplain, Nurse Cavell said, “I have no fear or shrinking; I have seen death so often it is not strange, or fearful to me.”

In Brussels, The German response was summed up as follows, “It was a pity that Miss Cavell had to be executed, but it was necessary. She was judged justly… It is undoubtedly a terrible thing that the woman has been executed; but consider what would happen to a State, particularly in war, if it left crimes aimed at the safety of its armies to go unpunished because they were committed by women.”

After the war, her remains were sent home. A monument was created in her memory. She was perhaps the most famous woman killed in the Great War. At the age of 49, she gave her life for her country and humanity, a loss no less than the sacrifices made by the most courageous of soldiers in battle.